The Comeback Kid: Jennifer’s Body – revaluated in the #MeToo era

‘This movie is art, but when it came out, nobody was saying that’, recalled Megan Fox in an interview with Washington Post in 2021. Instead, Jennifer’s Body, the smart, subtly scathing critique of the abuse young girls are subjected to by the patriarchy, was initially misunderstood and consensually dismissed as trash. Released in 2009 under a misplaced advertising campaign and at the height of the vitriolic backlash against its young star (Fox), the film grossed just $6.8 million in its opening weekend. However, in recent years Jennifer’s Body has been reclaimed by its intended audience and is heralded as a feminist cult classic. Although arguably, as Fox often says, ‘I don’t even know if it is cult anymore, it has grown so, so much.’ Now known for far more than the iconic meme of Megan Fox holding a lighter to her tongue, the film is appreciated for its dark and quirky exploration of the themes of abuse and female empowerment that were brought under the spotlight during the #MeToo movement.

Jennifer’s Body, written by Diablo Cody and directed by Karyn Kusama, focuses on two female high school girls, Jennifer Check (Fox) and her childhood best friend Anita Lesnicki (nicknamed ‘Needy’) played by Amanda Seyfried. Despite visibly displaying all the hallmarks of the stereotypical female duo so often found in films: the hot, popular ‘queen bee’ and her nerdy, needy best friend, these two characters refuse to conform and subvert this dynamic throughout the film.

The pair attend the concert of an indie boy band Low Shoulder at their local bar which proceeds to burn down during the performance. In the aftermath of the fire Jennifer is persuaded to go with the band, despite Needy’s warnings, and returns later that night visibly traumatised. The explanation behind this change, the keystone to understanding the entire plot, does not come until near the end of the film. In a brutally violent flashback, it is revealed that the members of Low Shoulder had attempted to sacrifice Jennifer, who they mistakenly believe to be a virgin, to Satan as an offering to help advance their careers. However, the ritual fails to kill Jennifer as she had in fact lost her virginity; a notable subversion of the trope in horror films which often sees the female protagonist ultimately saved by her chastity.

Instead, she becomes possessed by a demon and must satisfy her newfound appetite for blood by devouring exclusively male victims on a monthly basis, an apparent ‘female vampire’ take on the menstrual cycle. This scene provides the explanation to Jennifer’s attacks on the boys in her school; far from the random acts of a teen vampire they are the enactment of a rape-revenge fantasy. The supernatural foundation of the film reveals itself as a vehicle to allow the possessed but ultimately empowered version of Jennifer to impart a manner of justice and accountability which she would have most likely failed to receive in the real world.

Nonetheless, her actual attackers appear to escape this brutal form of justice and indeed capitalise upon the tragedies of the film, whilst Jennifer is eventually killed by Needy to stop the bloodshed. That is until it is revealed through CCTV footage during the end credits that Needy tracked Low Shoulder down and murdered them all in their hotel room.

The ability of the exaggerated nature of the genre of horror to offer derisive critiques of society is well understood in such prestige horror films as Jordan Peele’s recent Get Out, which was met with resounding acclaim. However, the key messaging of Jennifer’s Body was, for the most part, completely overlooked by contemporary critics. One of the more positive reviews of Jennifer’s Body at the time of its release described the film as ‘Twilight for boys’. However, the contrast between the unmatched level of disdain shown by Robert Pattison towards the Twilight franchise which made him famous and Fox’s evident love for an ‘iconic’ film which initially flopped points to the longevity and importance of Jennifer’s Body’s underlying themes.

Arguably, Cody’s distinctive style of witty, satirical dialogue, which won her an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for Juno in 2007 and features heavily in Jennifer’s Body, is less effective in this film as a vehicle to advance its key themes. The noisiness of the script has the potential to drown out the messaging and detracts from the silencing of the two female characters by the abuses they suffer at the hands of the patriarchy. However, the collective cultural reckoning that followed in the wake of the #MeToo movement saw the spotlight blazoned onto the very themes that were explored by the film a decade earlier. Frustratingly, these issues were ever-present when it was first released; however, they have been brought into focus and emerge from the film’s dialogue sharper and with greater cultural resonance as a result of this movement.

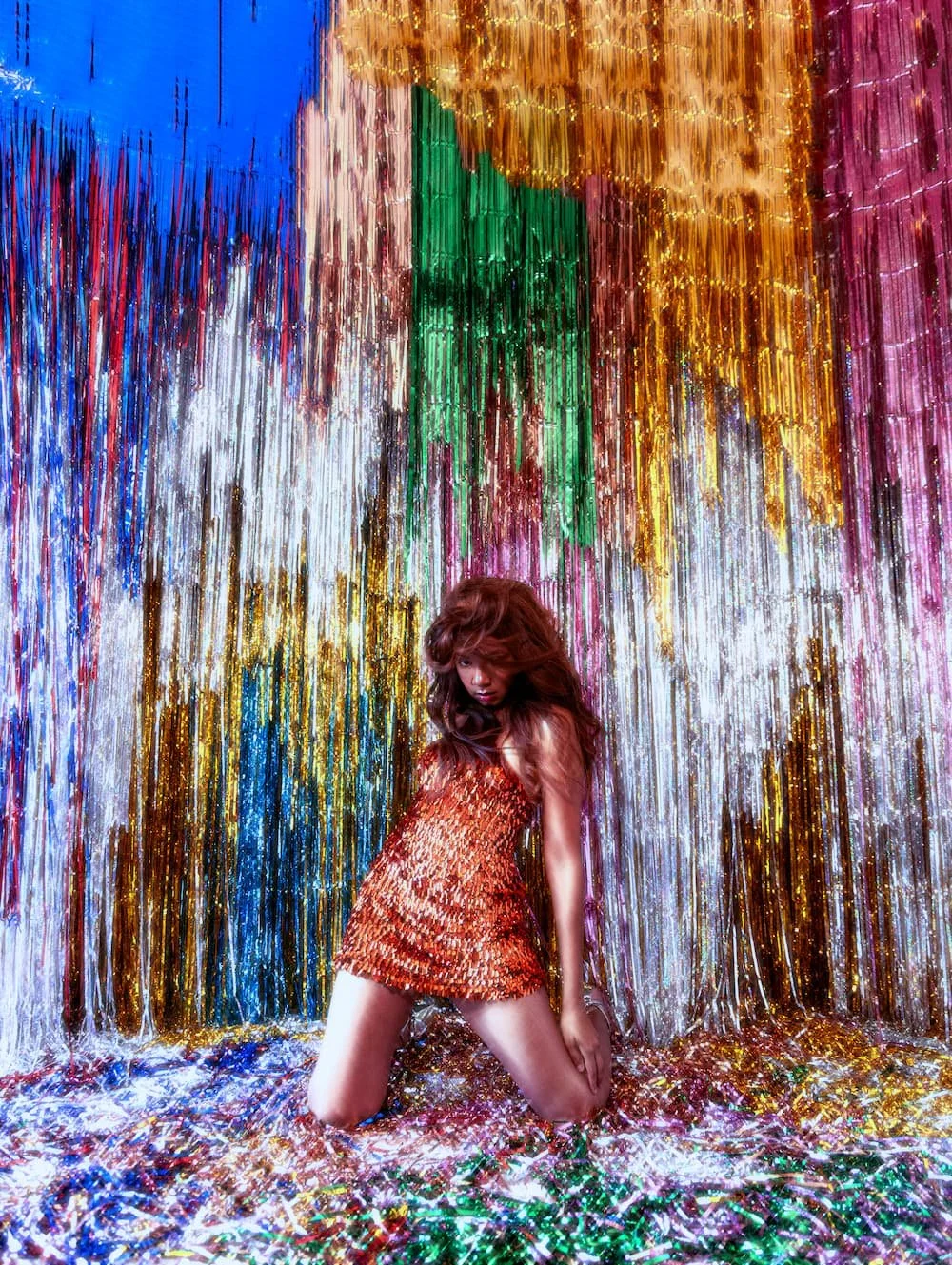

Additionally, the reaction to and subsequent re-appraisal of Jennifer’s Body and Megan Fox has brought to life some of the very themes the film explored. After years of hiding Fox has been experiencing a long-overdue and well-publicised renaissance. This has followed a collective re-evaluation of the way she, along with other young, heavily sexualised female stars, were treated by Hollywood. In a recent interview with In Style, Fox explained that ‘I hid because I was hurt’. Whereas the film’s iconic line says ‘hell is a teenage girl’, Fox describes the struggle of existing in the ‘horrendous, patriarchal, misogynistic hell that was Hollywood at the time’.

The actress has since re-claimed her narrative and her image after years of having one projected onto her by people who could not see past her sex appeal. To an extent, the messaging of the film overpowers its other elements, especially the characters who are held hostage to its themes. The titular Jennifer’s body is no longer her own, or perhaps never truly was, and as such she, like Fox experienced, remains a cipher onto which others project their own image onto her. We fail to grasp who she truly is and as such, the emotional weight of her untimely death is somewhat thwarted.

Needy defies all the conventions of the shy nerdy best friend, and yet her storyline remains dominated by and exists only in parallel to that of her more desirable friend. However, Needy reclaims the narrative at the end of the film, emerging as its heroine, by enacting the final act of revenge in honour of the late Jennifer. Thus, highlighting perhaps the most defining feature of both characters, they were each other’s best friend, for as Needy says, ‘sandbox love never dies’.

The importance and meaning of Jennifer’s Body lies in the illustration of its core themes. Even if these powerful ideas are not realised to their full potential, it remains unsettling and disturbing in its prescience. Remarking on the development of its cult following, director Kusama said ‘it’s the same movie, it’s the movie we always made, and it was the movie we always wanted to make. And maybe it just came several years too early’.

The sense of female empowerment and anger laced through the film has resonated with its audience today in a way that it failed to over a decade ago. Undoubtedly the cultural shift initiated by the #MeToo movement has brought the film into sharper focus. Its intrigue today also lies in its comeback. For the film’s very history now advances its messaging; revealing how society’s attitude at the time of its release towards such patriarchal abuse shown in the film, and inflicted on its young star, caused many to fail to appreciate this film for what it is; art.

(Jennifer’s Body is now available on Amazon Prime.)

Written by Maddy Briggs