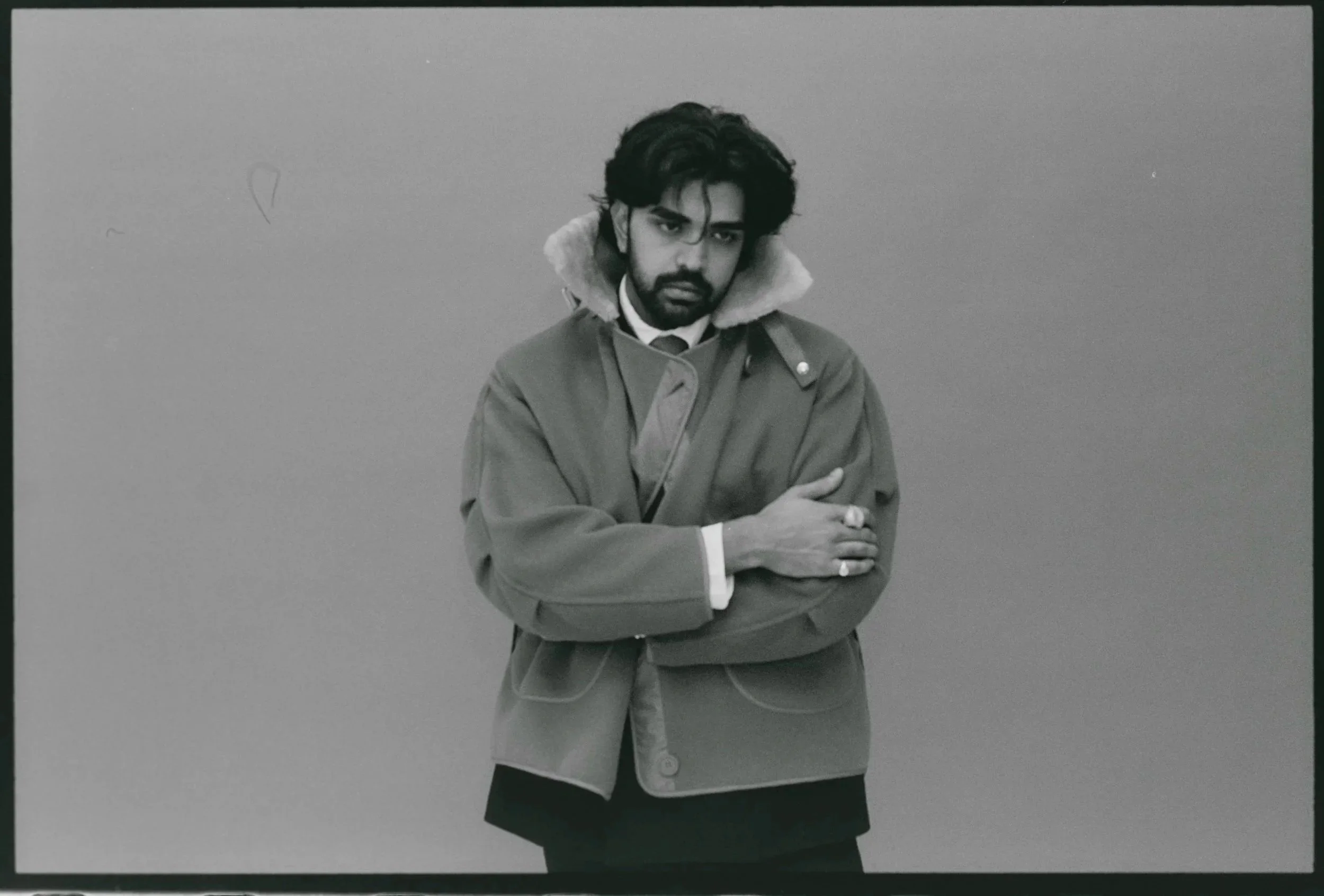

Talking to: Renao

Photography by Ed Cooke

Renao’s new album Still Life marks a turning point, with the goal of being a musician whose identity isn’t fixed to a genre but to a presence, a voice. This spirit guides Still Life, an album where the connective tissue isn’t style, but Renao himself. The record grew out of a difficult year: visa issues, mental health struggles, management changes, and the looming reality of finding another profession. It was a year that stripped things back to instinct, forcing him to ask what he wanted to sound like when nothing was guaranteed.

The answer emerged slowly, through experiments in R&B, folk, and electronic textures; through sessions in London and LA with Daniel Memmi and Leon Vynehall; through a widening musical curiosity that pushed him beyond his early influences. Still Life captures the messy, nonlinear path of rebuilding, where an artist lets his voice be the anchor while everything else keeps shifting.

His first performance of the album carried that same air of experimentation and dedication to art, hopping from mic to various instruments under a yellow spotlight. The acoustics of St Matthias Church made for a raw and heartfelt performance littered with impressive vocals and personal anecdotes for the audience.

What was your goal with Still Life?

I like making music that goes from one end to the other, and I kind of feel like that's what Still Life is. If you just listen to the intro and outro, they’re two completely different sounds, but my voice links them together. My priority was to push myself sonically. I might have a thousand ideas happening at the same time, but my voice is the thread that connects everything. That’s how I believe great music comes together.

Favourite song on the album?

Runtime is a great one to sing, for me it has a timeless quality, it sounds like a 70s song. Like the Baby song, I think I would enjoy singing it for the rest of my career. It's just so simple, outside of my vocal stacks, it's like six of things. piano bass and then we added some sax at the end to tie it all together.

Is there a song from the album that has grown on you the most?

Say it with your dress. Everyone around me wanted that song on the album but I couldn’t see it initially, it just felt too pop for the kind of music I wanted to make. Maybe it was to do with the production process, but now I see its place on the record and I really appreciate it as a song.

How has your music style developed and changed over the years?

When I moved to the UK in 2018, I fell in love with Frank Ocean, Tyler The Creator, and Brockhampton, who were my initial inspirations. So naturally, I was emulating them. In 2023, I decided maybe I need to listen to music outside of my usual tastes because I felt like I got stuck in a cycle. Growing up I never really liked radiohead, I wasn't into it, the music felt too dark for me. Five years later, I put on a radiohead song and I thought ‘wow, something in this is really interesting - is it the chords? the structures of it?’ and that’s how I started to find the nuances I liked in music outside my usual taste. I started listening to Nick Drake, folk singers, and then using Spotify radio to find as many different things as possible. Then suddenly the concept of Still Life emerged from all of that.

I have this notion that as long as your taste keeps getting wider and wider, you will never become the artist that you want to be. You will always be experimenting, trying to level up as an artist, and you will never stop expanding. It could be something so outside of your genre, like a classical piano piece where the guy’s going crazy, and you’ll think ‘I need to get to that level’. I feel like that's gonna be the chase for the rest of my life, and it’s a beautiful thing.

How did your version of Don & Joe Emmerson’s ‘Baby’ come about?

We got in direct contact with Don and sent him an email with the song because we needed him to clear it and he was super, super helpful. He really loved the song and said ‘I’m really happy, you have my blessing.’ I think he really liked the fact that people still appreciate his music, so it was great to have his blessing in that way. If you listen to my old catalogue then So Baby, then Still Life, you can see that song as a transitional bridge.

Why did that song resonate with you so much?

Don & Joe’s father didn't have a lot, but he still did everything he could to make sure that his children found a way to succeed. The reason that story is so compelling to me is because, despite all of it, their father had no hesitations. My dad didn't really have the means to send me to the UK for my career but he did anyway. I could have done a music degree in a small college in India and figured it out. I was making EDM, so I could have just been a DJ somewhere in India and made a decent living. But the fact that my dad tried his hardest to send me abroad, with way more foresight than I ever had, is what made me relate to that story so much. A parent putting their life on the line to make sure that their children can chase their dreams. Another part that moved me is as an artist, you are taught that if success doesn't come immediately, it's just never going to happen. The beauty of their story is you could live for 25 years not knowing that your music has touched a single soul, and then one day, you wake up and you realise it's hit 20 people, 100 people, and then suddenly your music is played by millions. That does something within you because I think artists can lose their confidence very easily. There is always a part of you that's slightly still delusional and believes there is a 0.1% chance that people everywhere are going to hear your music. When that moment finally happens, it's the most rewarding experience, because your hard work feels justified. The song had a certain impact, because as a musician, I want to be impactful in whatever way I can be.

A lot of your discography is R&B whereas ‘Still Life’ seems to take a risk and blur the lines between genres. Does it ever scare you to take risks?

Essentially this album to me is a reintroduction of the kind of artist I want to be, and I want people to be surprised with my choices. Some of the greatest artists are people like Rosalia where with every album, people go, ‘I like the old songs until the new ones come out’. I listened to Berghain and I wasn't sure if I liked it - but that's a really good thing. It starts with the strings and then she’s singing operatic German - you are like ‘‘what the fuck’ and then Yves Tumour comes in, it’s just crazy. It definitely got me really excited for her album. It’s a song that you listen to a couple times before you get it, but I like that feeling and I hope that my album also feels like that to people when they listen. ‘I don't know if I like this or not’ - and that's a good thing! Music should feel that way. When music clicks instantly that's great, maybe Runtime is one of those songs. But the song She was so terrifying to a lot of people around me because they thought this is not what you usually do with your music.

How did you build the album, was it a compilation of songs across the years or were you intentional in your creation process?

They were all new songs made for the album. I’ve had the album name for a really long time. Three years ago, I made this painting, cut out different pieces from magazines and stuck it on. I cut out this one piece that read ‘Still Life’, and that's where I got the name from. I would look at that painting every day and see ‘Still Life’. Before a single song on this album was ever made, we sold t-shirts that said Still Life - I just knew it was the right name. Sonically, the record is inspired by RnB, folk, and electronic music. I really love Big Thief. Adrienne Lenker is one of the best writers out right now, so they were a big inspiration. Still Life was born from all these sessions of just experimenting with new sounds and ideas in London and LA over a few months. I don't feel like I have songs sitting around. I only write when it definitely has to be written.

What was the production process like for Still Life?

Sonically, I prefer a warmer tone, so my choice of microphone was very intentional, and then we added these weird electronic textures. A lot of the album was produced by Daniel Memmi, who said ‘I have no rules in my playbook’, so we would just go into the studio and see what we could create, no matter how random or unpolished it was. I bought a little strum machine called the Digitakt, which has loads of random weird sounds. If you imagine a room, with a bunch of different gear everywhere, we would run past each, playing random things and recording it all. So we had a collection of random specific sounds and snippets that we cut and chopped. Then back in London we started working with Leon Vynehall, who was initially in my reference list of the type of music I wanted to emulate on this album, so it was a surreal moment to have him be a part of it. The foundation of that kind of production style was we didn’t have to speak about anything - we both knew which direction we were going in. I think all three of us kind of just knew we were just going to chuck everything we can at this, and then start taking it down from there. I love making music with other people because I can kind of just vomit stuff out and figure it out later, whereas if I'm on my own, I judge everything that comes out of me. Memmi said ‘I have no rules in my playbook’.

What makes you use your falsetto a lot across the album whilst also dipping into your lower register. What makes you want to play around with vocal decisions?

I think that comes from being a producer first, because I'm looking at my voice as an instrument and seeing what I can get out of it. I think of myself as coming through the School of R&B in some way. A song like Pressure did so well because it’s my falsetto. But a lot of folk music I was listening to tends to not go to falsetto. For example John Martin, he tends to go low with his voice and it’s amazing, so I was just playing with that side of my voice on the album too.

How does being an Indian artist influence you?

At the beginning of my career it was definitely something I tied my career to. I had a couple of moments on Instagram with Pressure and Jasmine, where a lot of the messaging was ‘hey, I'm an Indian artist who etc etc’. In a lot of ways, I felt like I had a responsibility to be a saviour, like I'm gonna be the artist that's gonna save the brown world and show the rest of the world that we can do this. Nowadays, I don’t want to be the ‘best brown musician’, I want to be the best. I don't want to be the biggest, making this album made me realise that. I just need to make the best music I can make. Whatever comes with it, comes with it, but I'm less worried about the fame and success. There's nothing to prove in terms of my skin colour, which used to be attached to identity for so long. I want being brown to be an afterthought and not the conversation starter.

Written by Melvin Boateng

Opinion