True Crime from An Inside Perspective: Robert Maltby On Surviving an Attack, And The Murder of His Girlfriend, Sophie Lancaster

True crime has been, in one form or another, a pretty stable source of entertainment for probably as long as civilisation has existed. From public trials and executions, through tabloid journalism, up through online platforms such as YouTube and Tiktok, it has endured. Unlike many other trends in entertainment, it endures. It is not too difficult to understand the appeal, even if it doesn’t entice oneself. It serves the whole gamut of interests, from a benevolent empathy for the victims, to the schadenfreude of seeing the suffering man can inflict upon his own kin. Really, I see its allure as a reminder that the base tedium of existence is not necessarily a permanent condition, even if the change would be markedly worse.

However, I have been on the other side of the camera, so to speak. In August 2007, myself and my then girlfriend, Sophie Lancaster, were attacked whilst out one night. For those unaware, we were attacked by five people in a park, leaving both of us in comas, from which only I was able to awaken. In the eighteen years that have passed since, this story has, like the medium of true crime, not really ever gone away. Most likely due to the actions of the foundation that was set up in Sophie’s name, the story has remained active in certain circles ever since, and new tellings of the story will periodically emerge.

I made a promise to myself, not long after Sophie’s death, that I would not exploit the story for profit. In the early days after the attack, I was inundated by media agencies begging me to spill my guts for a bit of money. This was not a source of entertainment for me, though; this was my life, and this was the life of the person closest to me permanently extinguished. My own morals were nothing in comparison to the demand for tales of human suffering, though.

I found the mental recovery from the event to be significantly impaired by not only its consistent presence, but also by its adaptation for the sake of entertainment. As is the case for any adaptation, there is an inevitable warping of the narrative for the sake of basic storytelling. There is, however, a significant difference between changing the details of a comic book and changing one of the most significant events in a person’s life, which they are still in the midst of processing.

As the retellings of this story continued, I found myself beginning to be written out of the narrative. As I had become frustrated by my difficulty in recovering, I became more vocal in my objections to having my memories put into the public domain. My desire was that the story could just be retired, as there is always fresh fodder for the troughs. This would mean I would have it back as my own memory, to understand and process in my own way. This was not the case, and my part began to become someone who was referred to as “the boyfriend”. This was something that I found not only severely insulting, but incredibly damaging. It is hard to describe what it feels like to become a side character in your own life.

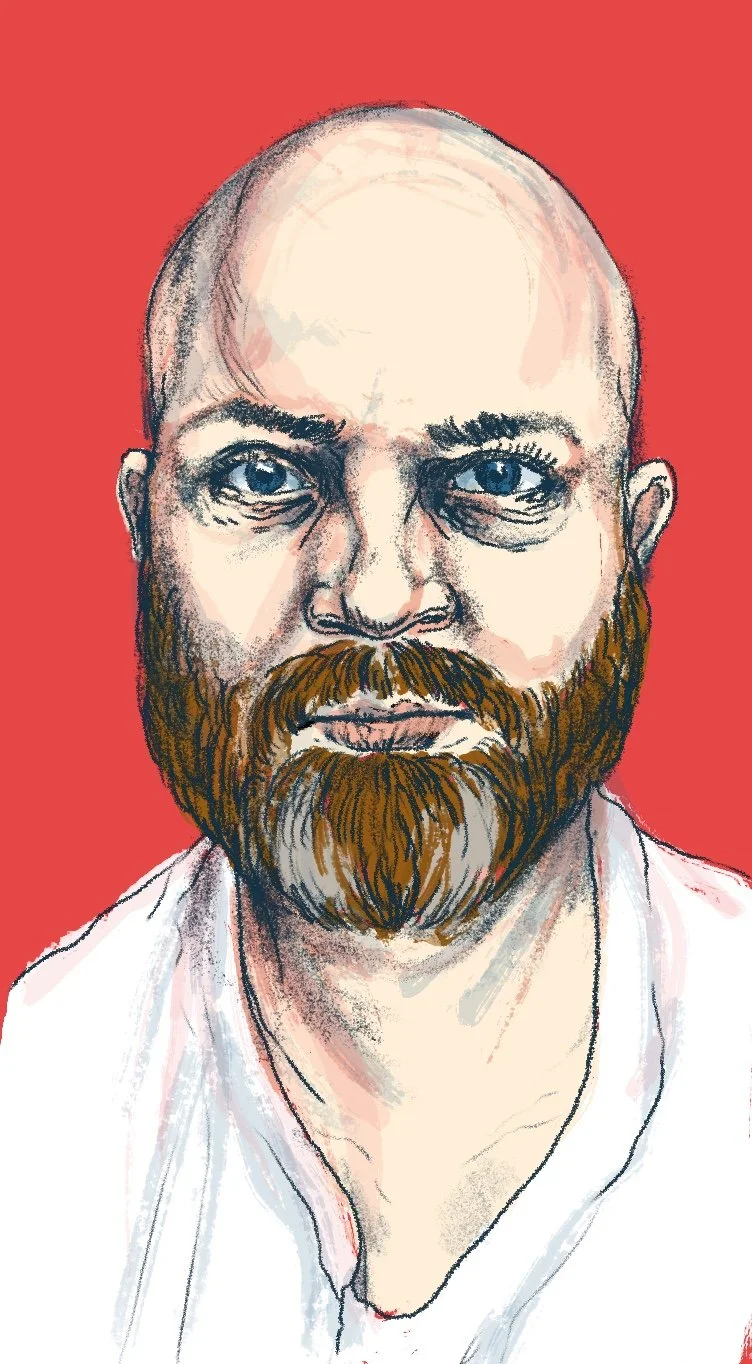

Illustration by Robert Maltby

What was a pivotal moment in my life was no longer mine. What was worse, the people intent on keeping their version alive did not do it out of a place of malice. If it was something that was being exploited for pure profit, then there would be a moral justification for my objections that were not derived from a place of selfishness. It is incredibly difficult to feel correct in wanting to retain hold of a memory when I am fully aware that it was not all about me. To take away Sophie’s family’s means of grief, no matter how misguided I may have found it, would have been an act of sheer avarice.

Really, though, it is hard to understate how much it can affect a mental recovery from a traumatic event, having the details altered in the public perception whilst it is still a constant presence in one’s psyche. As ridiculous as it may sound, it threw out my perception of myself entirely, to the point where I felt like I wasn’t real. This didn’t help with the fact that I was forced through psychological and financial reasons to be living at home in the countryside, when I was at the age where all of my closest friends were at university. I lost the entirety of the first half of my twenties, and many close friends, and this story had taken on a life of its own, from which people seemed to be deriving genuine pleasure and community.

I understand that the circumstances of our case have extended a certain cache that people have found compelling. This being that it has been marketed as someone who was, to quote the title of the 2018 BBC drama, murdered for being different. The dramatic hook of someone having been murdered for being dressed in an alternative fashion really does engender empathy, especially considering how anyone who has chosen a non-traditional form of self-expression has experienced some form of ignorance. I always felt, though, that the means of marketing this has always been poorly considered. The language, inevitably, implies that the onus of responsibility lies with the victim, and not with the perpetrators. I appreciate that it lacks romance to focus more on the socio-economic reasons for people to feel that it is a justifiable act to take the life of another, but this just goes back to my objection to the dramatisation of real life events.

When a story is put into the public like this, it creates a whole manner of preconceptions about those involved. What is the main idea is that it is implied that all of those involved will not only approve of its presence, but will actively support it. Whilst many have, it made my own desire for privacy even more difficult to maintain. This is not something unique to my own experience, as when the Netflix adaptation of the Jeffrey Dhamer case was released in 2022, many people related to the victims were incredibly vocal about their disapproval.

Regarding the aforementioned TV drama, Murdered For Being Different: this is the only dramatisation that I chose to provide any consultation. This show was made at the ten year anniversary of our attack, and it felt like a good opportunity to present a more accurate presentation of events. I wanted to present something that was more accurate, and, as such, respectful to Sophie. Every other piece based on the attack felt like a masturbatory deification of someone who was, at the end of the day, a human being. I wanted this one to show that this was real people living real lives, both out of this level of respect, and also for my own sake. I wanted to feel a connection to it all again, and not be a background character in a self-indulgent fairytale.

Whilst the drama was the best I could have hoped (and clearly the best adaptation from a critical perspective, being that it was the one that garnered a BAFTA), I don’t think it was ever possible for me to feel satisfied. I remember at the time, in some manner of interview, saying that it was as close to reality as it could have been whilst still remaining entertaining. I don’t know if there was ever going to be a circumstance under which I would be 100% behind an adaptation, though. As much as I wanted to create something that reflected my truth, I was also inclined to contribute because I knew that the adaptation was inevitable, regardless of my contribution.

Really, all I would like to say about true crime as a medium is that there are going to be people for whom this is not entertainment. I fully understand human curiosity, but to take tacit ownership of other people's lives through consumption of inevitably inaccurate accounts is a truly bizarre form of entertainment.

Illustration and words by Robert Maltby

Robert Maltby is an illustrator, painter and writer from Lancashire, currently based in London. He makes a living as an urban gardener and lives with his fiancée and young son. He creates posters for comedy shows and gigs in his spare time.